The story goes that it wasn’t always artificial red food dye that made a red velvet cake red.

The “velvet” portion of the name refers to the fact that this is a small-crumbed soft cake made with cocoa powder. A “velvet cake” is lighter and fluffier than, say, a pound cake. Velvet cakes rose in popularity in the Victorian era.

The original Red Velvet Cake was not artificially bright red, but merely had a reddish tint to the crumbs due to a chemical reaction caused by the combination of buttermilk, cocoa powder, and baking soda in the batter. That hint of rouge distinguished the red velvet cake from the deep brown color of a devil’s food cake (which is also a “velvet” cake, but has melted chocolate in the batter instead of buttermilk).

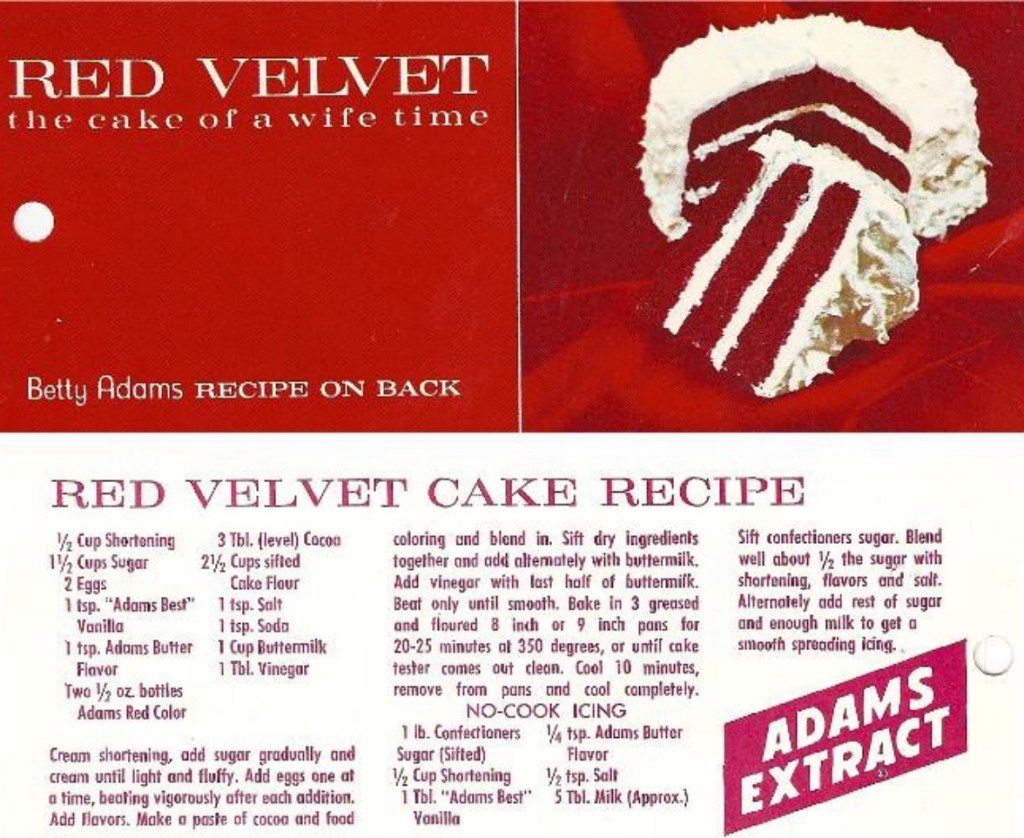

When did red velvet become a dye-fest? Well, it’s hard to say… but the Adams Extract & Spice company advertised their recipe for a red velvet cake using their red dye in the 1930s. It was, according to the card, “the cake of a wife time”. Adams placed displays with tear-off recipe cards near their products and were quite successful at making sales. The Adams “wife time” recipe card found its way into many American kitchens. The cake became so common that by 1972 three versions were featured in the book American Cookery by James Beard.

The most common dye in the U.S., Red Dye Number 40, wasn’t introduced until 1971 — but it’s what you’ll find in nearly every boxed Red Velvet cake mix you can find today.

Red Dye 40 is one of those things I avoid casually. By casually, I mean when it’s time for Christmas cookies, it’s easy enough to swap out my set of artificial food dyes for an all-natural set (like these), but I haven’t sworn off the occasional bag of red hot Cheetos. I don’t think Red Dyes 40 is good for me, but neither is the phone radiation I’m being exposed to as I write this. What can I say? Being alive will kill ya.

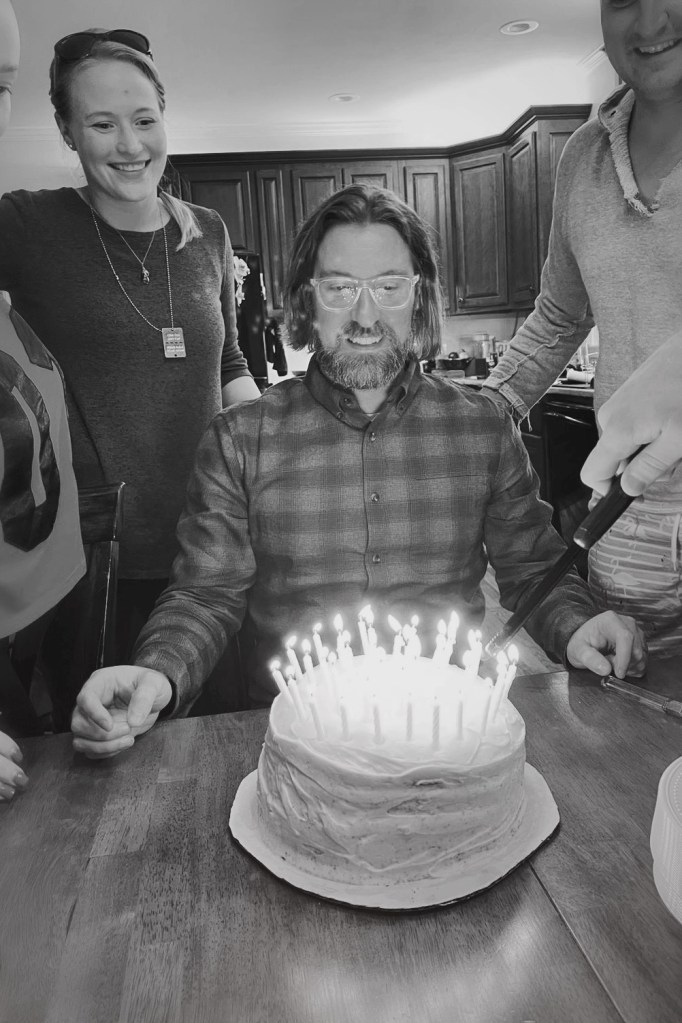

When I discussed the above historical trivia with the Birthday Boy, he voted to try a recipe iteration following in the original “rusty” reddish-brown tradition. Using buttermilk, of course.

I opted to diverge from historical tradition when it came to the frosting. Most historic recipes recommend “Ermine” frosting, also known as a Boiled Milk Frosting, whereas the modern frosting of choice is Cream Cheese. I love cream cheese frosting more than cake itself (and Scott agreed), so the modern frosting stayed.

I’m not going to link you to the exact recipe I tried, because I think it turned out just a little too crumbly. I’ll be hunting for another version that holds together slightly better next time, but regardless, it was delicious. It’s pretty hard to go wrong with buttermilk, vanilla, sugar, eggs, cake flour, oil, baking soda, and vinegar (ok yeah, that last ingredient is weird, but no flavor of vinegar was noted to be present in the end result). Topped with cream cheese frosting, of course.

Happy 38th to the Love of my Life.

I love you more than ever.